Library of Congress

In May 2012, a researcher working for The Papers of Abraham Lincoln project discovered a document in the National Archives many historians knew existed but had never found. It was the initial account of army surgeon Charles A. Leale who was the first physician to attend the assassinated president at Ford’s Theatre on the evening of April 14, 1865.

Although Leale had detailed the event and his participation in three other documents – an 1867 account for a congressional committee, a case report in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, and an address delivered in New York in 1909 – the newly located account was reportedly written by Leale within hours of Lincoln’s death. Even though the account reveals little new information, it remains an interesting narrative of the tragic events of that spring night in 1865.

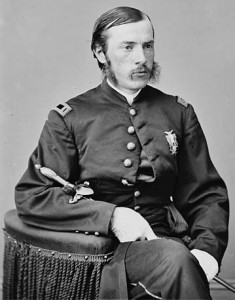

Charles A. Leale was a 23-year-old Assistant Surgeon in the U.S. Army Volunteers who had just received his medical degree six weeks earlier. He had been assigned to duty as the surgeon in charge of the Wounded Commissioned Officers’ Ward at the General Hospital at Armory Square in Washington, D.C. Leale decided to attend the April 14 performance of Our American Cousin because he had heard that President Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant would be there. As it turned out, Lincoln and his party would arrive late and without Grant, who had been unable to attend.

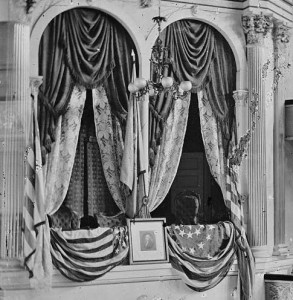

According to Leale, he was seated only 40 feet from the presidential box and was enjoying the performance when, suddenly, “the report of a pistol was distinctly heard.” He then saw John Wilkes Booth leap from the box and onto the stage with a dagger in his hand. Upon next hearing shouts that the president had been murdered, the young physician quickly ran to the box where he found Lincoln “seated in a high backed arm-chair with his head leaning towards his right side supported by Mrs. Lincoln who was weeping bitterly.”

Library of Congress

Lincoln was unconscious, breathing intermittently, and had no discernible pulse. With the help of two other gentlemen, Leale laid the president on the floor in a recumbent position. As he was doing so, his hand came in contact with a clot of blood near Lincoln’s left shoulder. Assuming that Lincoln had been stabbed by the dagger he had seen in Booth’s hand, Leale cut open the president’s coat and shirt to examine the shoulder. After finding no shoulder wound, he examined Lincoln’s head “and soon passed my fingers over a large firm clot of blood situated about one inch below the superior curved line of the occipital bone.”

Removing the clot of blood, Leale discovered a hole in the skull and introduced the small finger of his left hand into the opening. To his dismay, he found that a bullet had penetrated the skull and entered the brain. Upon removing his finger, a slight oozing of blood flowed from the hole, and Lincoln’s breathing suddenly became easier. Physiologically, Lincoln’s brain had been swelling due to the accumulation of blood from the injury. The increased pressure within the enclosed skull was compressing the brain and interfering with its functions, primarily respiratory stimulation. By removing the obstructing clot, Leale had inadvertently reduced the pressure in the brain by allowing the free flow of blood out of the confined space.

Lincoln was carried from the theater to the Petersen house across the street and placed diagonally across a bed as the president’s six-foot-four inch frame was too large to fit otherwise. Upon removing Lincoln’s clothes, Leale found the president’s “lower extremities very cold from his feet to a distance several inches above his knees.” He ordered hot water bottles and blankets to be placed on Lincoln’s abdomen and lower extremities.

At 11:00 p.m., Leale and the other physicians who had arrived noticed signs of continued bleeding within the skull – bruising around both eyes from blood tracking into the soft tissues. Additionally, the right pupil was dilated and the eye itself began to protrude slightly outward.

The surgeons realized that Lincoln’s wound was fatal and spent the rest of the night, and into the next morning of April 15, 1865, keeping the opening in the skull “free from coagula, which if allowed to form and remain for a very short time, would produce signs of increased compression: the breathing becoming profoundly stertorous and intermittent and the pulse to be more feeble and irregular.”

Library of Congress

Leale then records Abraham Lincoln’s final hours:

At 1 A.M. his pulse suddenly increasing in frequency to 100 per minute, but soon diminished gradually becoming less feeble until 2.54 A.M. when it was 48 and hardly perceptible.

At 6.40 A.M. his pulse could not be counted, it being very intermittent, two or three pulsations being felt and followed by an intermission, when not the slightest movement of the artery could be felt. The inspirations now became very short, and the expirations very prolonged and labored accompanied by a gutteral sound.

6.50 A.M. The respirations cease for some time and all eagerly look at their watches until the profound silence is disturbed by a prolonged inspiration, which was soon followed by a sonorous expiration.

At 7.20 A.M. he breathed his last and “the spirit fled to God who gave it.”

In his published 1909 address before the Commandery of the State of New York Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Leale described his somber mood following the president’s death:

I left the house in deep meditation. In my lonely walk I was aroused from my reveries by the cold drizzling rain dropping on my bare head, my hat I had left in my seat at the theatre. My clothing was stained with blood, I had not once been seated since I first sprang to the President’s aid; I was cold, weary and sad. The dawn of peace was again clouded, the most cruel war in history had not completely ended.

Charles Leale continued to serve in the army until 1866. He then returned to his home town of New York City where he established a successful private practice and became involved in charitable medical care. One of the last surviving witnesses to Lincoln’s death, Dr. Charles A. Leale died in 1932 at the age of 90.

I have an original 4 page hand written letter by dr. Charles Leale written to mr. Littlefield, describing in great detail the last hours of President Lincoln.

Interesting. Do you know if it contains additional details not present in Dr. Leale’s other writings?

This is really great information. I wish young people would be as interested in history these days. The information here is something someone cannot forget especially if interested. Abraham Lincoln stood out as one of the most famous and popular presidents we have had.